Chapter 5: Additional Topics

5.1 Polar Coordinates

Introduction

Up to now we have done all our work in this course and previous courses in the Cartesian Coordinate system. This is the square grid where we have an \(x\)-axis and a \(y\)-axis and every point in the plane can be described by using two pieces of information: distance traveled in the \(x\) direction and distance traveled in the \(y\)-direction. The points and their distances from the origin are indicated as an ordered pair \((x, y)\).

While this system of identifying points on the plane is quite useful it is not the only way to do so. Another way is the use of polar coordinates. Polar coordinates are drawn in the plane starting at a fixed point \(O\) called the pole or origin and a ray in the positive \(x\) direction called the polar axis. Polar coordinates also use two pieces of information to identify a point in the plane:

\(\theta\): an angle measured from the polar axis

\(r\): a directed distance from the pole.

Figure 5.1 shows a point in the plane identified with both coordinate systems. In polar coordinates the point is \((r, \theta)\). In Cartesian coordinates it is useful to draw a square grid to measure distances in the \(x\) and \(y\) directions but this grid is not what we need for polar coordinates. In polar coordinates we have concentric circles that represent the radii and lines extending out radially indicating the angles. See Figures 5.2 and 5.3 for two different versions. You can mark the angles in either degrees or radians but radians is the most common. We will primarily use radians for all our work with polar coordinates in this text.

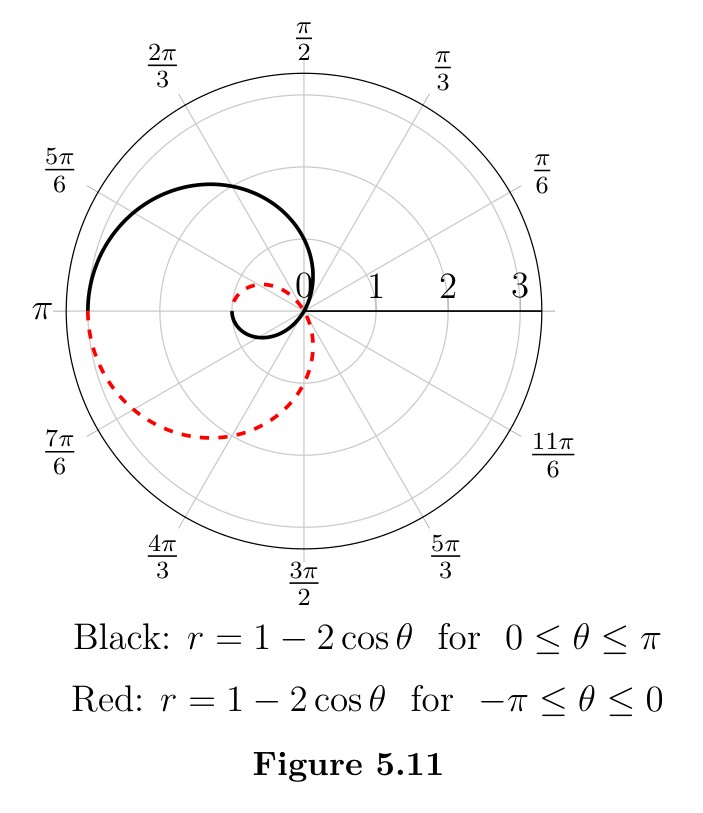

The angle \(\theta\) can be both positive and negative just as when constructing reference angles. When positive, it is measured starting at the polar axis traveling in the counter clockwise direction and, when negative, it is measured in the clockwise direction. The radius \(r\) is called a directed distance because it can also be positive or negative. If it is positive it is measured from the origin in the direction of the angle and if negative it is measured in the opposite direction. See Example 5.1.1.

Converting Between Cartesian and Polar Coordinates

To convert between the coordinate systems we will use a triangle. By drawing a triangle on our previous representation of a point on the plane we can use the trigonometric functions and the Pythagorean theorem to relate \(x\), \(y\), \(r\) and \(\theta\).

Converting Between Cartesian and Polar Equations

Graphing Polar Equations

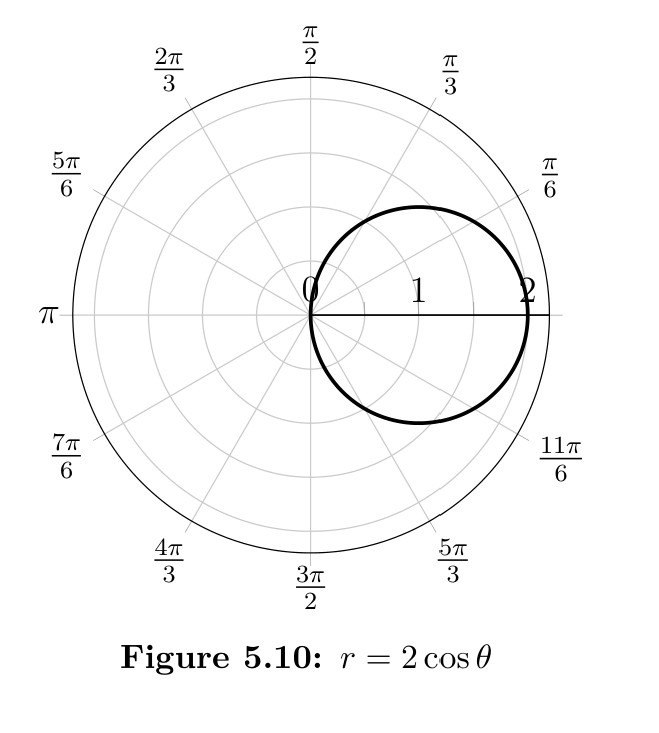

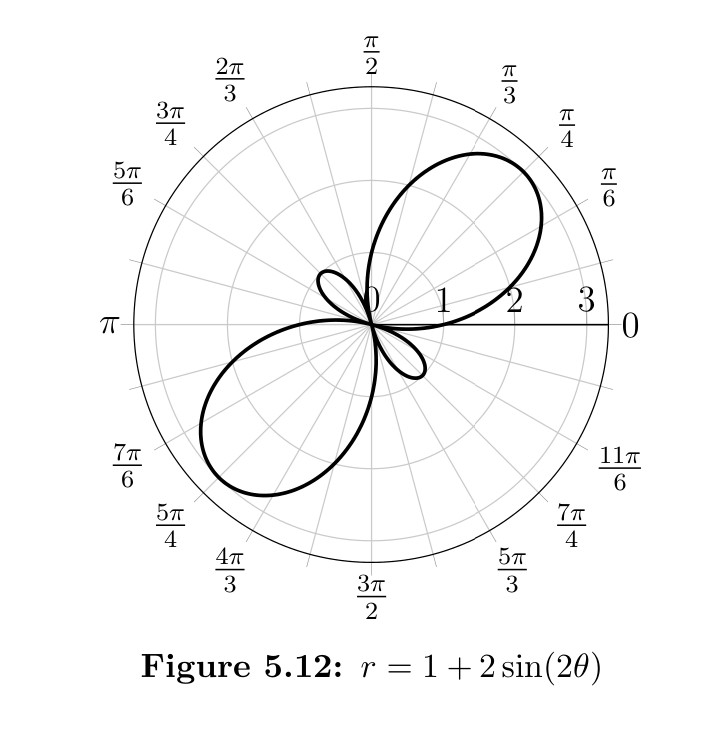

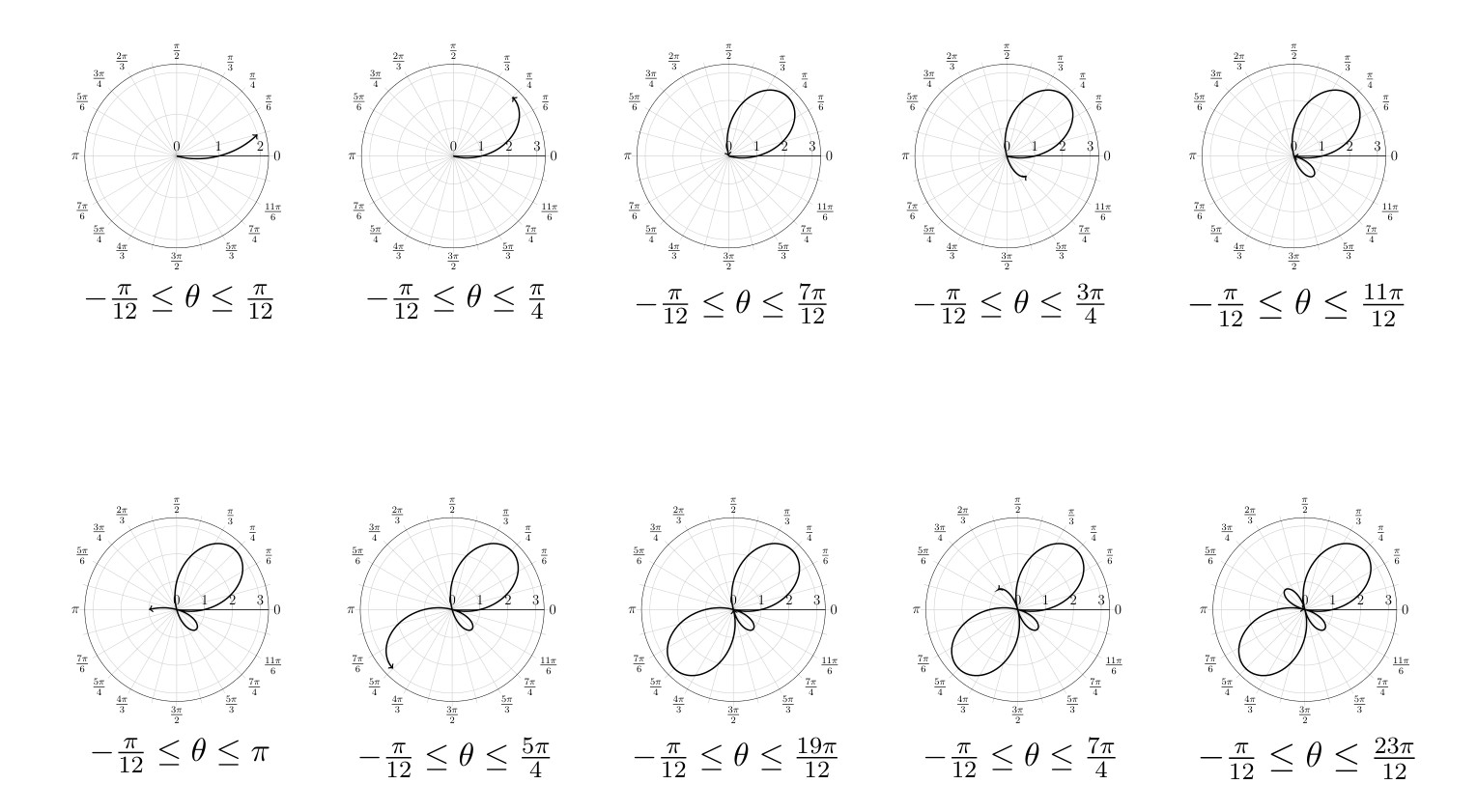

The process of sketching this figure is shown below. The process of sketching the points in order, with a smooth curve, is demonstrated through the 10 diagrams in Figure 5.12.

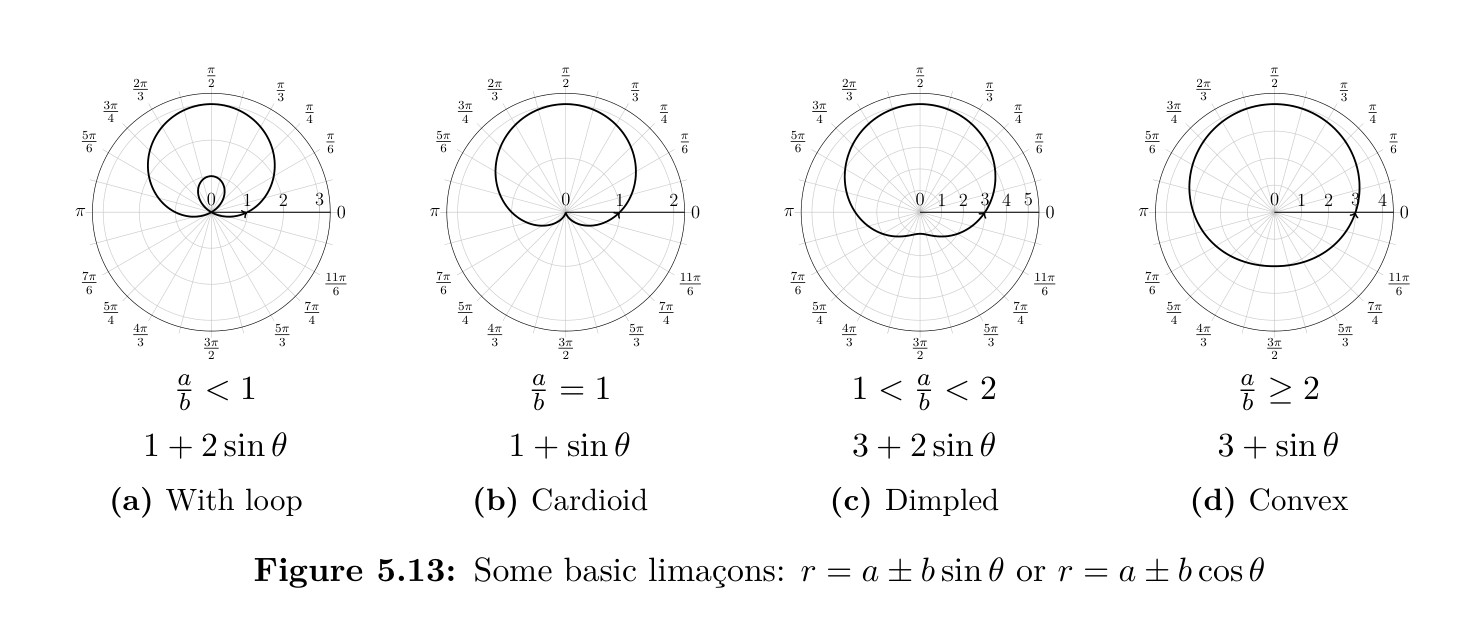

There are some general shapes that the polar graphs can have. The figure drawn in Example 5.1.8 is called a limaçon and is the name given to any curve with an equation of the form \(r=a \pm b \sin \theta\) or \(r=a \pm b \cos \theta\). The limaçon can take on one of four shapes depending on the relationship between \(a\) and \(b\). See Figure 5.13. The limaçon will be symmetric with the vertical axis if it is a sine graph and symmetric with the horizontal if a cosine graph.

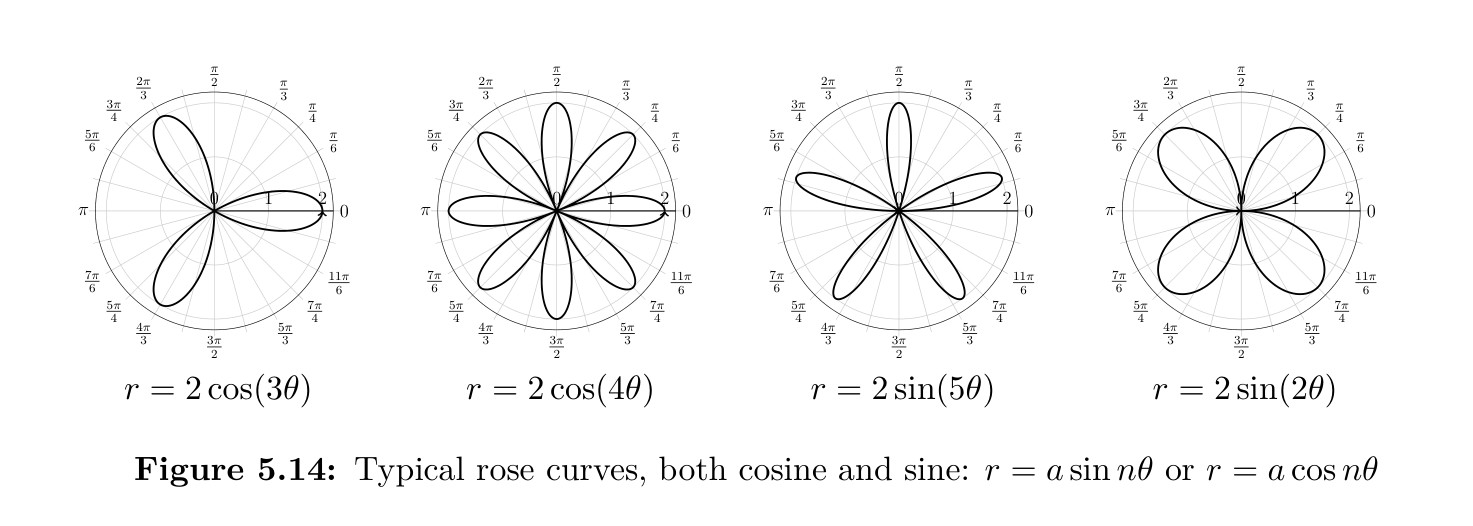

Another typical shape with polar graphs is the rose shape. This was demonstrated in Example 5.1.9. The rose curve comes from equations of the form \(r = a \cos(n\theta)\) or \(r = a \sin(n\theta)\) and the rose has \(n\) petals if \(n\) is odd and has \(2n\) petals if \(n\) is even.

5.1 Exercises

For Exercises 1-8, plot the point and convert from polar to Cartesian coordinates.

\((4, 210^\circ)\)

\(\left(5,\dfrac{7\pi}{6}\right)\)

\(\left(5,\dfrac{3\pi}{4}\right)\)

\(\left(3,\dfrac{-3\pi}{4}\right)\)

\(\left(4,\dfrac{7\pi}{3}\right)\)

\(\left(-5,\dfrac{11\pi}{4}\right)\)

\(\left(-3,\dfrac{-3\pi}{4}\right)\)

\(\left(2, \dfrac{\pi}{2}\right)\)

For Exercises 9-16, convert from Cartesian to polar coordinates.

\((6,2)\)

\((-1,3)\)

\((1,1)\)

\((-3,-3)\)

\((-7,-1)\)

\((1,-\sqrt{3})\)

\((-3\sqrt{3},-3)\)

\(\left(-\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}, \dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\right)\)

For Exercises 17-22, convert the Cartesian equation to a polar equation.

\(y=3\)

\(y=x^2\)

\(x^2+y^2=9\)

\(x^2+y^2 = 9y\)

\(y = \sqrt{3}x\)

\(5y+x+2=0\)

For Exercises 23-28, convert the polar equation to a Cartesian equation.

\(\theta = \dfrac{\pi}{4}\)

\(r=4\cos \theta\)

\(r = 5\)

\(r = -6\sin \theta\)

\(r = \dfrac{4}{\sin \theta + 7 \cos \theta}\)

\(r = 2\sec \theta\)

For Exercises 29-37, sketch the graph of the polar equation.

\(r=4\cos \theta\)

\(r = -6\sin (2\theta)\)

\(r = 3\sin (5\theta)\)

\(r=4+4\cos \theta\)

\(r = 1+2\cos (2\theta)\)

\(r = 3\cos (3\theta)\)

\(r = 5\)

\(r = 2 + 4 \sin \theta\)

\(\theta = \dfrac{\pi}{4}\)

5.2 Vectors in the Plane

Introduction

We deal with many quantities that are represented by a number that shows their magnitude. These include speed, money, time, length and temperature. Quantities that are represented only by their magnitude or size are called scalars. When you travel in your car and you look at the speedometer it tells you how fast you are going but not where you are going. This is a scalar value and is called the speed.

A vector is a quantity that has both a magnitude (size) and a direction. To describe a vector you must have both parts. If you know that you are traveling at 150 mph north then that would be a vector quantity and it is called the velocity. It tells you how fast you are traveling, speed is 150 mph, as well as the direction, north.

Vector Representations

When we write a vector there are two common ways to do it. If we want to talk about “vector \(v\)” we can either write the \(\mathbf{v}\) in bold or write the \(\vec{v}\) with an arrow over it. In this text we will most often use the arrow notation but do be aware that the bold notation is also common.

To describe a vector we need to talk about both the magnitude and direction. The magnitude of a vector is represented by the notation \(||\vec{v}||\). The direction can be described in different ways and depends on the application. For example you might say that a jet is traveling in the direction \(10^\circ\) north of east, or a force is applied at a particular angle or with a particular slope.

A vector can be represented by simply an arrow: in Figure 5.15 the vector \(\vec{v} = \overrightarrow{PQ}\) which starts at point \(P\) and ends at point \(Q\) has magnitude equal to its length (\(||\vec{v}||\)) and direction as indicated. The vector can be moved around in the plane as long as the length and direction are unchanged. All the vectors in Figure 5.15 are equivalent because they all have the same length and point in the same direction. When the vector is drawn this way the length is always the magnitude. An accurate picture is necessary to accurately describe a vector this way. Sometimes it is called a directed line segment.

A vector drawn starting at the origin is in standard position as shown in Figure 5.17. A vector in standard position has initial point at the origin \((0,0)\) and can be represented by the endpoint of the vector \((a, b)\). This is known as representing the vector by components: \(\vec{v} = \langle a, b \rangle\). It is common to see this written as \(\vec{v} = \langle v_x, v_y \rangle\). Notice the use of “angle brackets” \(\langle ~ \rangle\) to write the vector. This distinguishes it from the point at the end of the vector. Writing a vector as components is generally preferable because it is easier to perform calculations with components rather than directed line segments. Also, while all the work in this book is with two dimensional vectors you can also write vectors in three or even more dimensions. It is very difficult to draw a directed segment in three dimensions while writing it with components is quite straight forward.

If you want to write \(\vec{v}\) from point \(P\) to point \(Q\) then \(\vec{v} = Q - P\). For example in Example 5.2.1, \(\vec{u} = \overrightarrow{PQ} =(1,4) - (-3,-2) = \langle 4,6 \rangle\). It is important to subtract in the correct order. It is always “end point” minus “starting point”. If you subtract in the wrong order you end up with a vector that has the same length but points in the opposite direction.

Vector Operations

There are mathematical operations that we can do with vectors. The two most common are multiplication by a scalar and vector addition. Recall that a scalar is a number. If you want to multiply a vector \(\vec{v}\) by a scalar \(k\) there are two ways to think about it. Multiplying by the scalar \(k\) does not change the direction of the vector but makes it longer or shorter by a factor of \(k\). If you have your vector written in components \(\vec{v} = \langle v_x, v_y \rangle\) then each component is multiplied by \(k\):

\[k \cdot \vec{v} = k\cdot \langle v_x, v_y \rangle = \langle k\cdot v_x,\ k\cdot v_y \rangle\]

Adding vectors can be done two ways. We can add vectors that are written as directed line segments or we can add them as components. If you wish to add \(\vec{u}\) to \(\vec{v}\) you draw \(\vec{v}\) and then draw \(\vec{u}\) so that the tail of \(\vec{u}\) starts at the head of \(\vec{v}\). You can see in Figure 5.20 that it does not matter in which order you do this. \(\vec{R} = \vec{u} + \vec{v} = \vec{v} + \vec{u}\)

If the vectors are written as components you can add the \(x\) components and the \(y\) components separately. The component operations are summarized below.

5.2 Exercises

For Exercises 1-2, write the vector shown in component form.

For Exercises 3-4, given the vectors shown, sketch \(\vec{u}+\vec{v}\), \(\vec{u}-\vec{v}\), and \(2\vec{u}\).

For Exercises 5-10, write the vector \(\vec{v} = \overrightarrow{PQ}\) in the form \(\vec{v} =\) (magnitude) \(\cdot\) (direction) where the direction is a unit vector. See Example 5.2.2.

\(P=(1,2)\), \(Q=(-2,3)\)

\(P=(-3,2)\), \(Q=(-3,3)\)

\(P=(0,1)\), \(Q=(-2,-7)\)

\(P=(-40,23)\), \(Q=(5, -5)\)

\(P=(-4,2)\), \(Q=(2, -3)\)

\(P=(1,2)\), \(Q=(0,0)\)

For Exercises 11-14, write the vector in component form from the given magnitude and direction.

Magnitude: 6; direction: \(30^\circ\)

Magnitude: 7; direction: \(120^\circ\)

Magnitude: 8; direction: \(225^\circ\)

Magnitude: 9; direction: \(330^\circ\)

For Exercises 15-18, given the vectors, compute \(3\vec{u}\), \(2\vec{u}+\vec{v}\), and \(\vec{u}-3\vec{v}\).

\(\vec{u} = \langle 2, -2 \rangle\), \(\vec{v} = \langle 3, 2 \rangle\)

\(\vec{u} = \langle 1, -2 \rangle\), \(\vec{v} = \langle -4, 2 \rangle\)

\(\vec{u} = \langle 2, -3 \rangle\), \(\vec{v} = \langle 1, 2 \rangle\)

\(\vec{u} = \langle 3, 4 \rangle\), \(\vec{v} = \langle 5, -6 \rangle\)

A woman leaves home and walks 3 miles west, then 2 miles southwest. How far from home is she, and in what direction must she walk to head directly home?

A boat leaves the marina and sails 6 miles north, then 2 miles northeast. How far from the marina is the boat, and in what direction must it sail to head directly back to the marina?

A person starts walking from home and walks 4 miles east, 2 miles southeast, 5 miles south, 4 miles southwest, and 2 miles east. How far have they walked? If they walked straight home, how far would they have to walk?

A person starts walking from home and walks 4 miles east, 7 miles southeast, 6 miles north, 5 miles southwest, and 3 miles east. How far have they walked? If they walked straight home, how far would they have to walk?

Three forces act on an object: \(\vec{F}_1 = \langle 2, 5\rangle\), \(\vec{F}_2 = \langle 8, 3\rangle\) and \(\vec{F}_3 = \langle 0, -7\rangle\). Find the net force acting on the object.

Three forces act on an object: \(\vec{F}_1 = \langle -2, 5\rangle\), \(\vec{F}_2 = \langle -8, -3\rangle\) and \(\vec{F}_3 = \langle 5, 0\rangle\). Find the net force acting on the object.

Suppose there are three forces acting on an object: a 10 Newton force acting at \(45^\circ\), a 20 Newton force acting at \(210^\circ\) and a 15 Newton force acting at \(315^\circ\). Find the resultant force vector acting on the object.

A person starts walking from home and walks 6 miles at \(40^\circ\) north of east, then 2 miles at \(15^\circ\) east of south, then 5 miles at \(30^\circ\) south of west. If they walked straight home, how far would they have to walk, and in what direction?

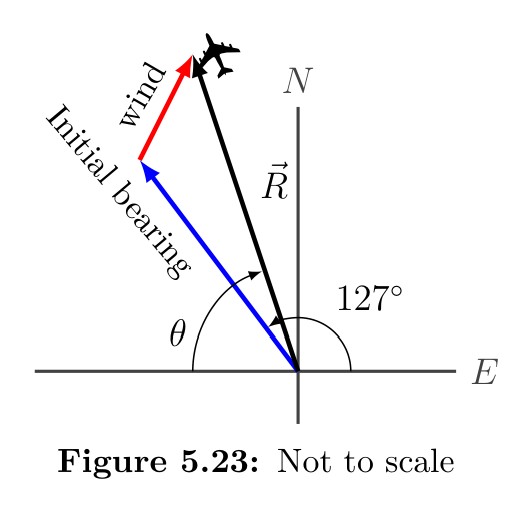

An airplane is heading north at an airspeed of 600 km/hr, but there is a wind blowing from the southwest at 80 km/hr. How many degrees off course will the plane end up flying, and what is the plane’s speed relative to the ground?

An airplane is heading north at an airspeed of 500 km/hr, but there is a wind blowing from the northwest at 50 km/hr. How many degrees off course will the plane end up flying, and what is the plane’s speed relative to the ground?

An airplane needs to head due north, but there is a wind blowing from the southwest at 60 km/hr. The plane flies with an airspeed of 550 km/hr. To end up flying due north, the pilot will need to fly the plane how many degrees west of north?

An airplane needs to head due north, but there is a wind blowing from the northwest at 80 km/hr. The plane flies with an airspeed of 500 km/hr. To end up flying due north, the pilot will need to fly the plane how many degrees west of north?

As part of a video game, the point \(\langle 5, 7 \rangle\) is rotated counterclockwise about the origin through an angle of 35 degrees. Find the new coordinates of this point.

As part of a video game, the vector \(\langle 7, 3 \rangle\) is rotated counterclockwise about the origin through an angle of 40 degrees. Find the new coordinates of this point.

Footnotes

A Newton (N) is a metric unit of force \(\text{N} = \frac{\text{kg} \cdot \text{m}}{\text{s}^2}\)↩︎