Chapter 1: Trigonometric Functions

1.1 Angles and Their Measure

Angles

We will usually draw our angles on the coordinate axes with the positive \(x\)-axis being the Initial Side. If we sweep out an angle in the counter clockwise direction we will say the angle is positive and if we sweep the angle in the clockwise direction we will say the angle is negative. An angle is in standard position if the initial side is the positive \(x\)-axis and the vertex is at the origin.

When representing angles using variables, it is traditional to use Greek letters. Here is a list of commonly encountered Greek letters.

| alpha | beta | gamma | theta | phi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| \(\alpha\) | \(\beta\) | \(\gamma\) | \(\theta\) | \(\phi\) |

Measuring an Angle

One Radian

When we measure angles we can think of them in terms of pieces of a circle. We have two units for measuring angles. Most people have heard of the degree but the radian is often more useful in trigonometry.

NOTE: By convention if the units are not specified they are radians.

Degrees: One degree (\(1^{\circ}\)) is a rotation of 1/360 of a complete revolution about the vertex. There are 360 degrees in one full rotation which is the terminal side going all the way around the circle.

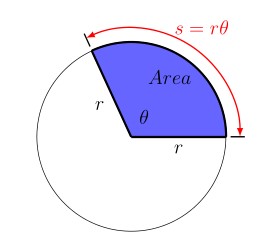

Radian: One Radian is the measure of a central angle \(\theta\) that intercepts an arc equal in length to the radius \(r\) of the circle. See Figure 2 at right. Since the radian is measured in terms of \(r\) on the arc of a circle and the complete circumference of the circle is \(2 \pi r\) then there are \(2\pi\) radians in one full rotation.

Since \(360^\circ = 2\pi\) radians, this gives us a way to convert between degrees and radians:

\[180^\circ = \pi \text{ radians}\]

If we sketch these two angles from Example 1.1.1 on a single graph and in standard position (Figure 4) we will see that they look exactly the same. Since these two angle terminate at the same place we call them Coterminal Angles.

Coterminal angles end up in the same position but have different angle measures.

There are an infinite number of ways to draw an angle on the coordinate axes. By simply adding or subtracting \(360^\circ\) (or \(2\pi\) rad) you will arrive at the same place. For example if you draw the angles \(240^\circ + 360^\circ = 600^\circ\) and \(-120^\circ - 360^\circ = -480^\circ\) you will end up in the same positions as the angles in Figure 4.

Degrees, Minutes and Seconds

The Babylonians who lived in modern day Iraq from about 5000BC to 500BC used a base 60 number system. It is believed that this is the origin of having 60 minutes in an hour and 60 seconds in a minute. This may also explain why our degree measures are multiples of 60, once around the circle is 6 60s. Similar to the way hours are divided into minutes and seconds the degree (\(^\circ\) ) can also be divided into 60 minutes (\('\)) and each of those minutes is divided into 60 seconds (\(''\)). This form is often abbreviated DMS ( \(^\circ\) \('\) \(''\) ).

Some Basic Angles

| Name of angle | Measure in degrees | Measure in radians |

|---|---|---|

| Right angle | \(90^\circ\) | \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) |

| Straight angle | \(180^\circ\) | \(\pi\) |

| Acute angle | between \(0\) & \(90^\circ\) | between \(0\) & \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) |

| Obtuse angle | between \(90\) & \(180^\circ\) | between \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) and \(\pi\) |

Some Special Angles

Two acute angles are complementary if their sum equals \(90^\circ\). In other words, if \(0^\circ \le \angle A, \angle B \le 90^\circ\) then \(\angle A\) and \(\angle B\) are complementary if \(\angle A + \angle B = 90^\circ\).

Two angles between \(0^\circ\) and \(180^\circ\) are supplementary if their sum equals \(180^\circ\). In other words, if \(0^\circ \le \angle A, \angle B \le 180^\circ\) then \(\angle A\) and \(\angle B\) are supplementary if \(\angle A + \angle B = 180^\circ\).

Two angles between \(0^\circ\) and \(360^\circ\) are conjugate (or explementary) if their sum equals \(360^\circ\). In other words, if \(0^\circ \le \angle A, \angle B \le 360^\circ\) then \(\angle A\) and \(\angle B\) are conjugate if \(\angle A + \angle B = 360^\circ\).

Notation: Notice that we use the \(\angle\) symbol here to denote angle \(A\). Very often we will drop the \(\angle\) symbol and simply refer to the angle by its letter if there is no chance for confusion. Angles are often labeled with Greek letters as seen earlier or with Latin letters as seen here. It is common to use upper case letters to denote angles but sometimes we use lowercase variable names (e.g. \(x\), \(y\), \(t\)).

Arc Length and Area

There is another way to define the radian. The radian measure of an angle is the ratio of the length of the circular arc subtended by the angle to the radius of the circle as seen in Figure 8. So the radian measure of an arc of length \(s\) on a circle of radius \(r\) is:

\[\text{radian measure} = \theta = \frac{s}{r}\]

which can be rewritten as:

\[s = r\theta\]

This is the arc length formula.

From geometry we know that the area of a circle of radius \(r\) is \(\text{area}=\pi r^2\). We want to find the area of a sector of a circle. A sector of a circle is the region bounded by a central angle and its intercepted arc, such as the shaded region in Figure 8. The area of this sector is proportional to the angle by the following relationship:

\[\begin{equation*} \frac{\text{sector area}}{\text{circle area}} = \frac{\text{sector angle}}{\text{one revolution}} = \frac{Area}{\pi r^2} = \frac{\theta}{2\pi} \end{equation*}\]

This gives a formula for the area of the sector of circle radius \(r\) with central angle \(\theta\):

\[\begin{equation*} Area = \frac{1}{2} r^2 \theta \end{equation*}\]

1.1 Exercises

For Exercises 1-20:

- draw the angle in standard position

- find two coterminal angles, one positive and one negative.

Leave your answer in the same units (degrees/radians) as the original problem.

- \(120^\circ\)

- \(-120^\circ\)

- \(-30^\circ\)

- \(217^\circ\)

- \(-217^\circ\)

- \(-115^\circ\)

- \(928^\circ\)

- \(1234^\circ\)

- \(-1234^\circ\)

- \(-515^\circ\)

- \(\frac{\pi}{2}\)

- \(\frac{5\pi}{3}\)

- \(-\frac{5\pi}{3}\)

- \(\frac{3\pi}{7}\)

- \(\frac{11\pi}{6}\)

- \(5\pi\)

- \(-17\)

- \(-\frac{35\pi}{3}\)

- \(-\frac{15\pi}{4}\)

- \(\frac{122\pi}{3}\)

For Exercises 21-32, convert to radians or degrees as appropriate. Leave an exact answer.

- \(120^\circ\)

- \(115^\circ\)

- \(135^\circ\)

- \(-425^\circ\)

- \(-270^\circ\)

- \(15^\circ\)

- \(\frac{\pi}{2}\)

- \(\frac{\pi}{3}\)

- \(\frac{\pi}{4}\)

- \(\frac{\pi}{5}\)

- \(-\frac{\pi}{6}\)

- \(-\frac{11\pi}{6}\)

For Exercises 33-36, write the following angles in DMS format. Round the seconds to the nearest whole number.

- \(12.5^\circ\)

- \(125.7^\circ\)

- \(539.25^\circ\)

- \(7352.12^\circ\)

For Exercises 37-40, write the following angles in decimal format. Round to two decimal places.

- \(12^\circ 12' 12''\)

- \(25^\circ 50' 50''\)

- \(0^\circ 22' 17''\)

- \(1^\circ 1' 1''\)

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan is located at \(52.1332^\circ\)N, \(106.6700^\circ\)W. Convert these map coordinates to DMS format.

On a circle of radius 7 miles, find the length of the arc that subtends a central angle of 5 radians.

On a circle of radius 6 feet, find the length of the arc that subtends a central angle of 1 radian.

On a circle of radius 12 cm, find the length of the arc that subtends a central angle of 120 degrees.

On a circle of radius 9 miles, find the length of the arc that subtends a central angle of 200 degrees.

A central angle in a circle of radius 5 m cuts off an arc of length 2 m. What is the measure of the angle in radians? What is the measure in degrees?

Mercury orbits the sun at a distance of approximately 36 million miles. In one Earth day, it completes 0.0114 rotation around the sun. If the orbit was perfectly circular, what distance through space would Mercury travel in one Earth day?

Find the distance along an arc on the surface of the Earth that subtends a central angle of \(1^\circ 5'\). The radius of the Earth is 6,371 km.

Find the distance along an arc on the surface of the sun that subtends a central angle of \(1''\) (1 second). The radius of the sun is 695,700 km.

On a circle of radius 6 feet, what angle in degrees would subtend an arc of length 3 feet?

On a circle of radius 5 feet, what angle in degrees would subtend an arc of length 2 feet?

A sector of a circle has a central angle of \(\theta = 45^\circ\). Find the area of the sector if the radius of the circle is 6 cm.

A sector of a circle has a central angle of \(\theta = \frac{10\pi}{7}\). Find the area of the sector if the radius of the circle is 20 cm.

1.2 Right Triangle Trigonometry

Pythagorean Theorem

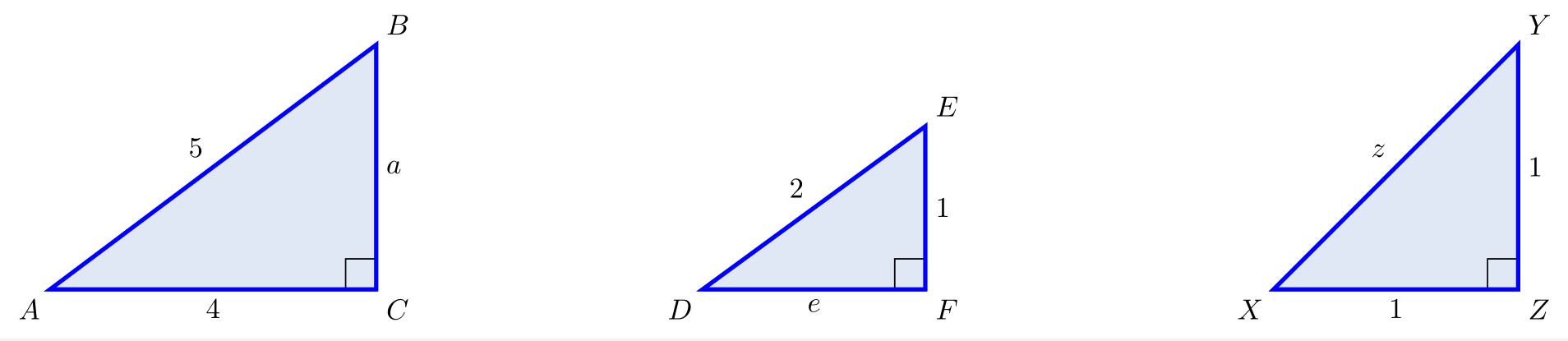

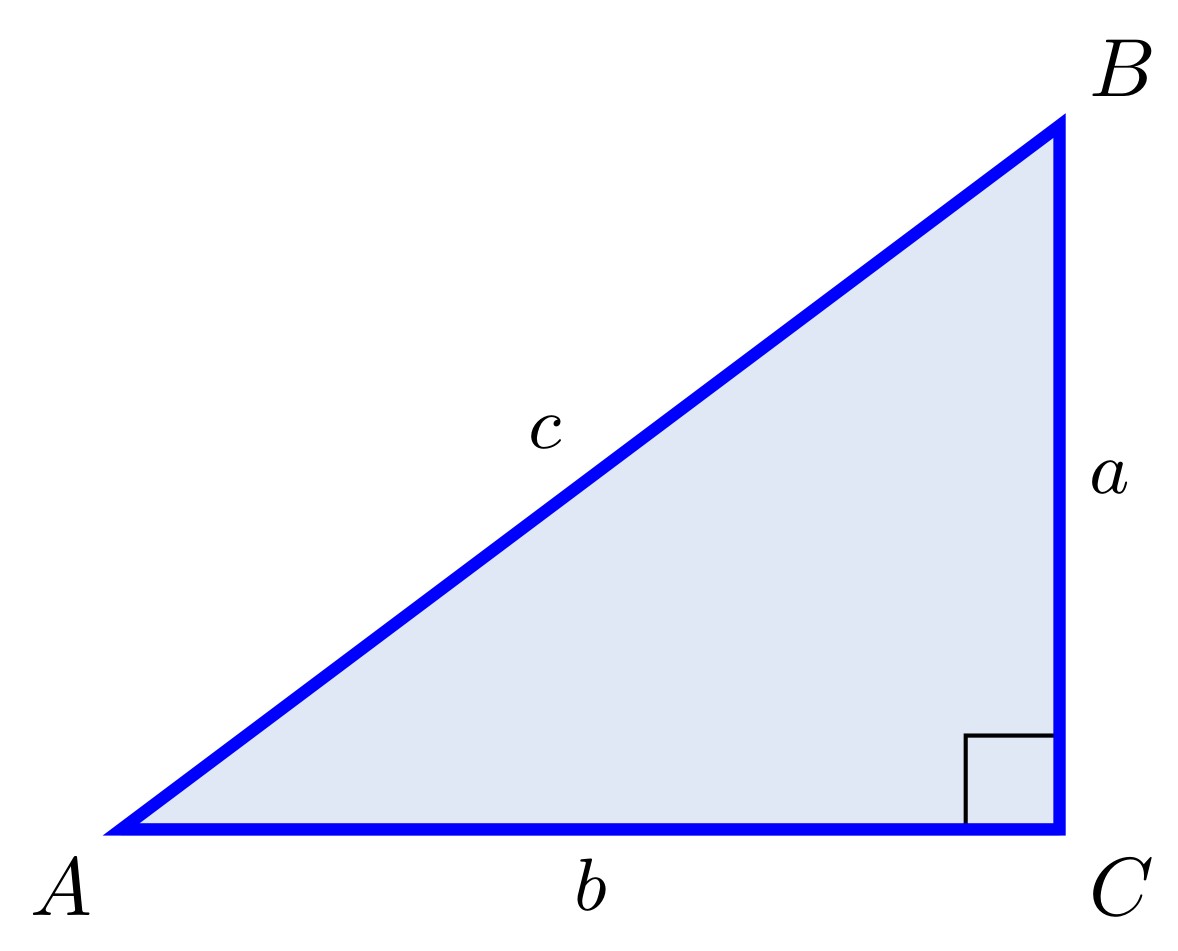

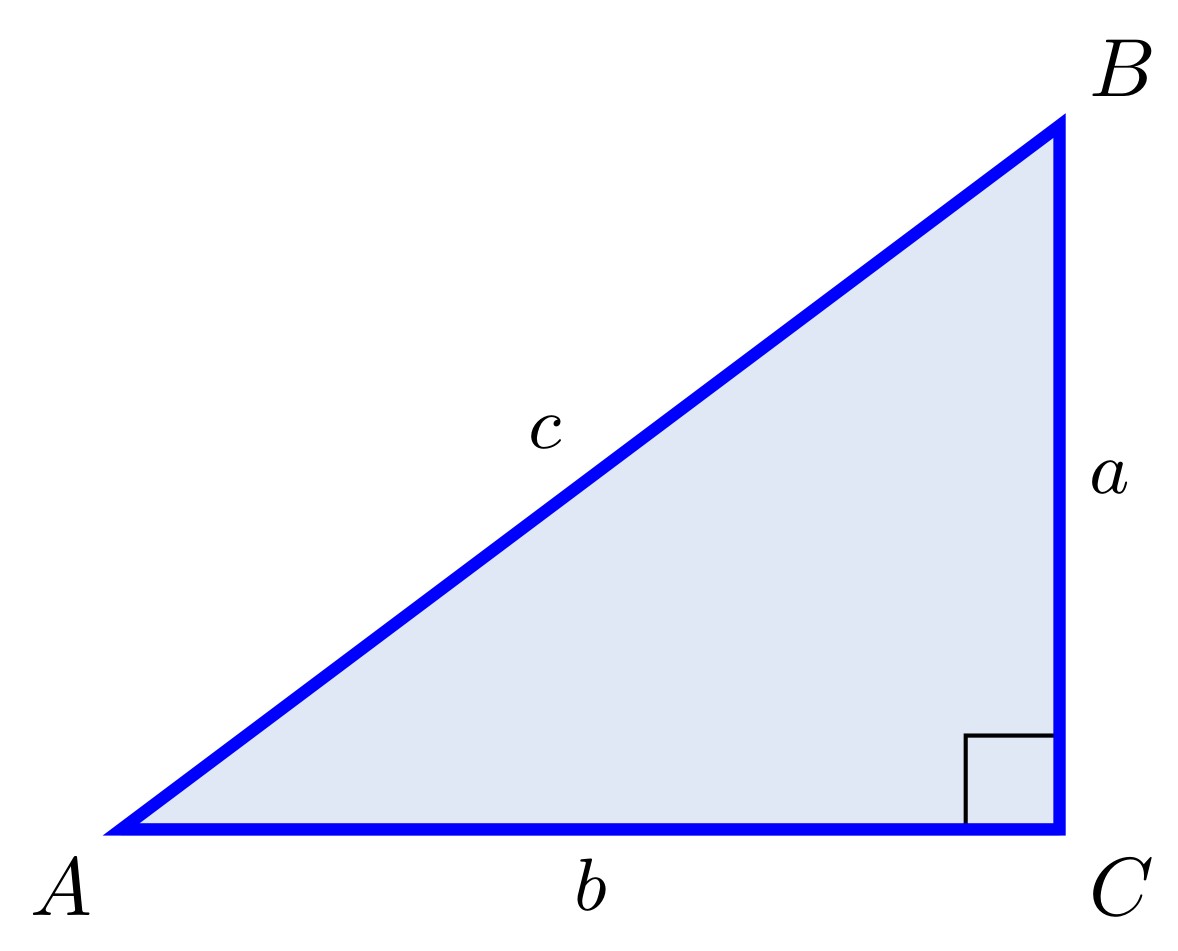

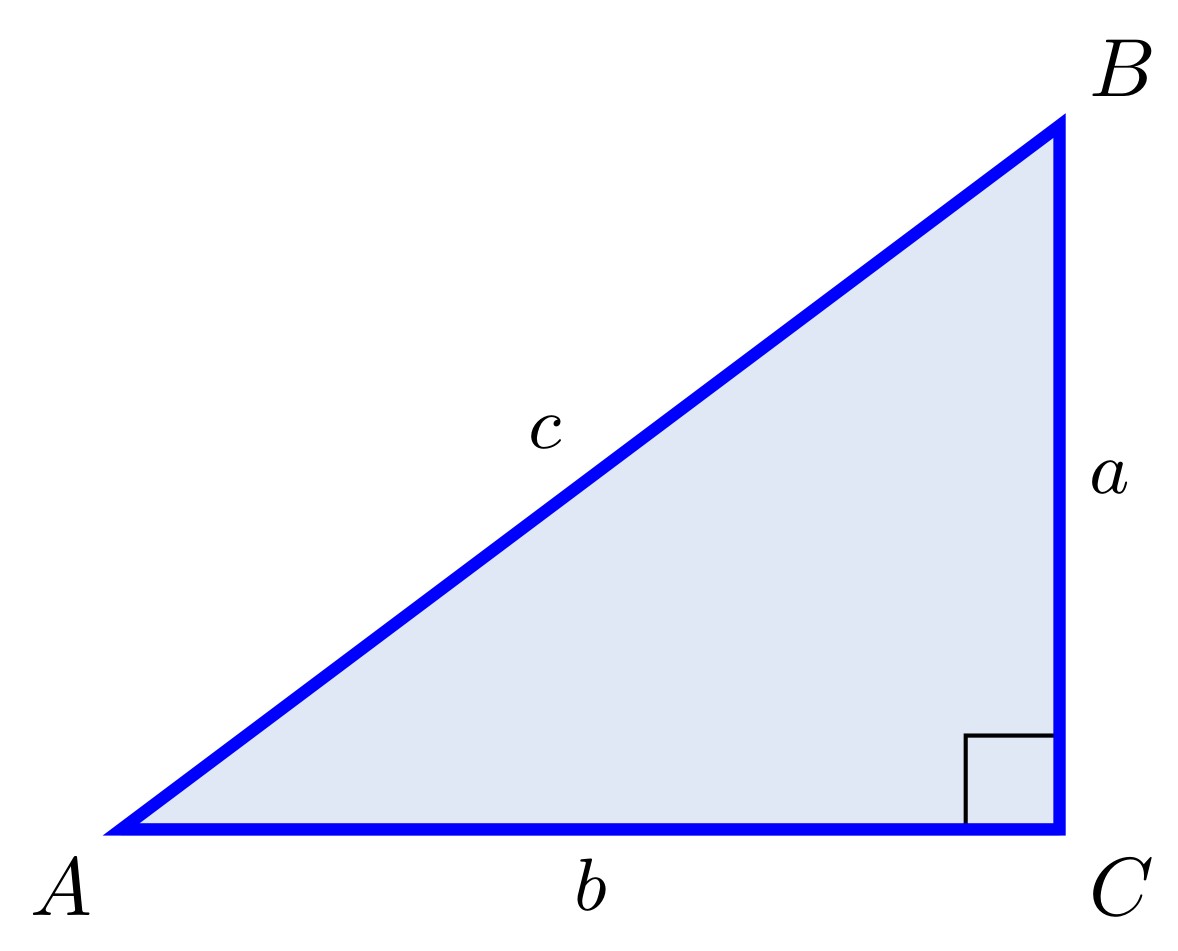

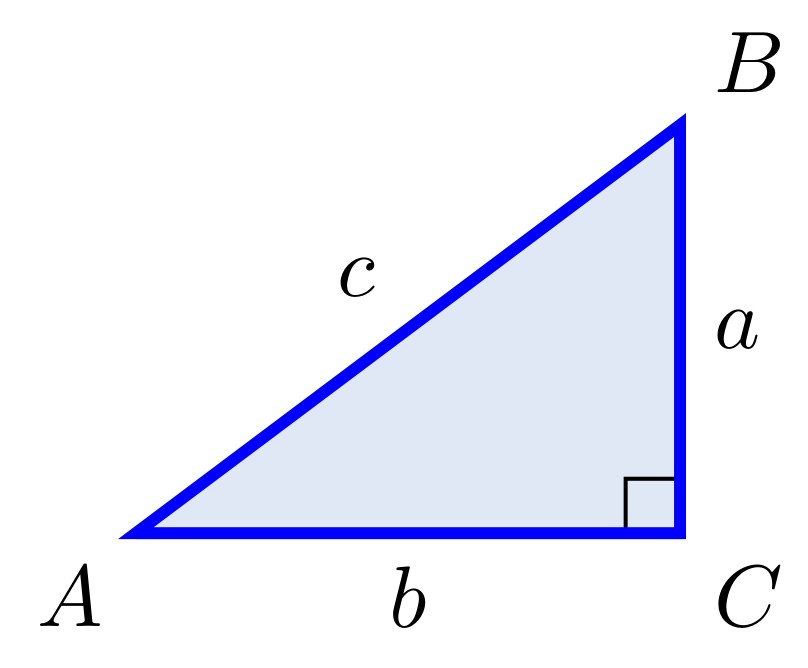

Figure 1.9: \(a^2+b^2=c^2\)

In a right triangle, the side opposite the right angle is called the hypotenuse, and the other two sides are called its legs. For example, in Figure 1.9 the right angle is \(C\), the hypotenuse is the line segment \(\overline{AB}\), which has length \(c\), and \(\overline{BC}\) and \(\overline{AC}\) are the legs, with lengths \(a\) and \(b\), respectively. The hypotenuse is always the longest side of a right triangle. When using Latin letters to label a triangle we use upper case letters (\(A, B, C, \ldots\)) to denote the angles and we use the corresponding lower case letters (\(a, b, c, \ldots\)) to represent the side opposite the angle. So in Figure 1.9 side \(a\) is opposite angle \(A\).

By knowing the lengths of two sides of a right triangle, the length of the third side can be determined by using the Pythagorean Theorem:

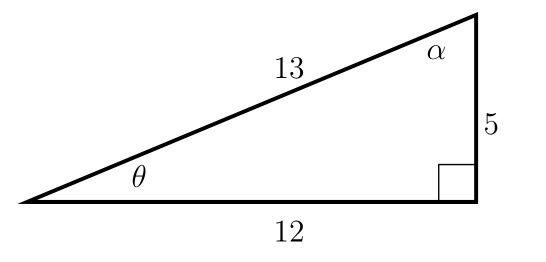

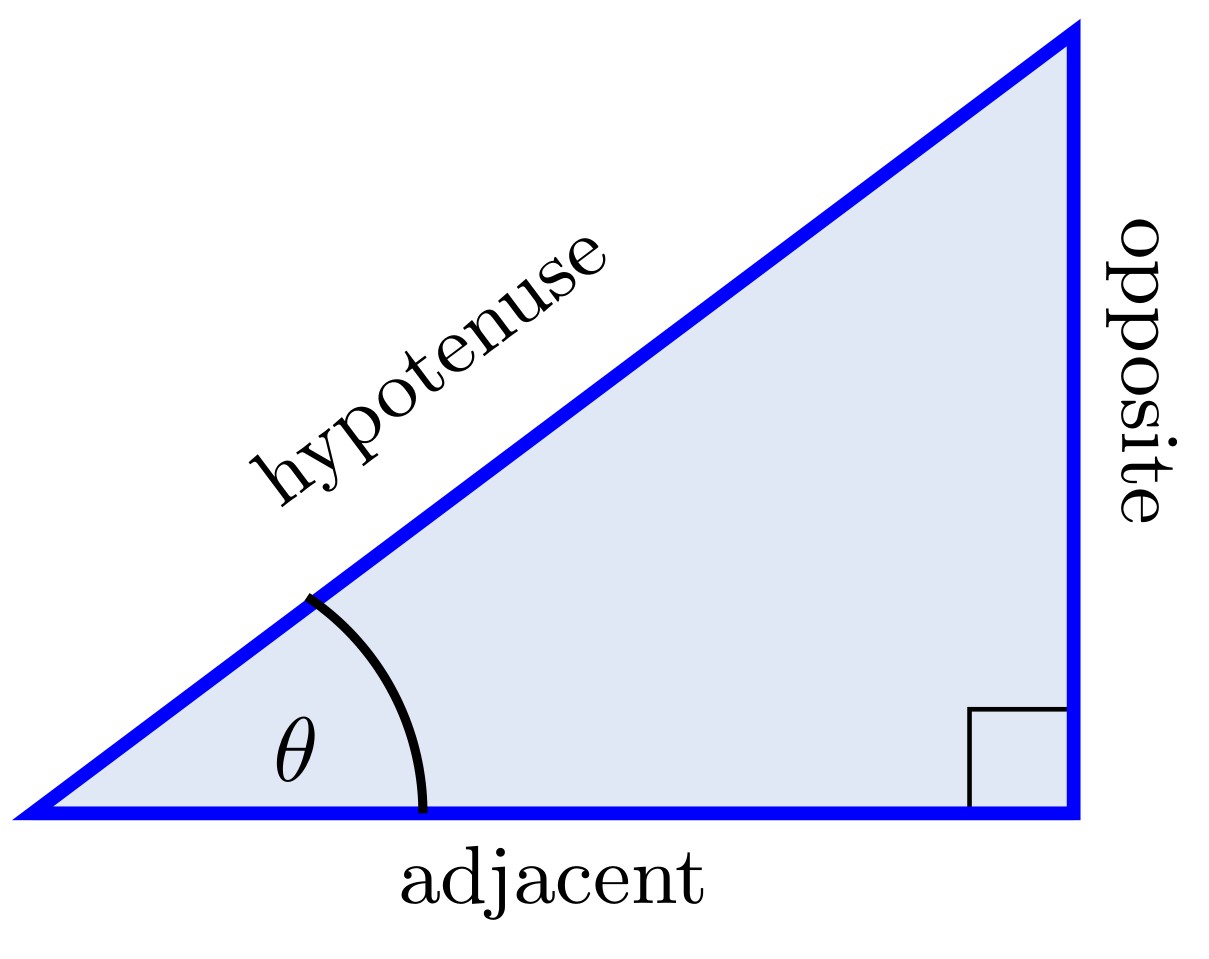

Basic Trigonometric Functions

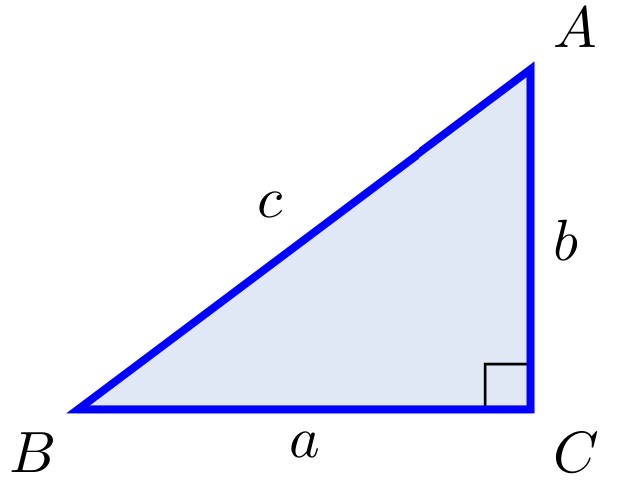

Consider a right triangle where one of the angles is labeled \(\theta\). The longest side is called the hypotenuse, the side opposite the angle \(\theta\) is called the opposite side and the side adjacent to the angle is called the adjacent side, see Figure 1.10. Using the lengths of these sides you can form 6 ratios which are the trigonometric functions of the angle \(\theta\). These ratios are irrespective of the size of the triangle. If the angles in two triangles are the same then the triangles are similar which means the ratios of the sides will be the same. When calculating the trigonometric functions of an acute angle \(\theta\), you may use any right triangle which has \(\theta\) as one of the angles.

Figure 1.10: Standard right triangle

We will usually use the abbreviated names of the functions.

Two Special Triangles

For the angles 45°, 30° and 60° we have two special triangles which allow us to find their trigonometric functions. To construct a right triangle with a 45° angle we will start with a square with sides of length 1 and cut it in half with a diagonal. Since the square is completely symmetric a diagonal will cut the angle in half creating two 45° angles. Consider the lower triangle in Figure 1.11. We found the length of the diagonal by the Pythagorean theorem. Then we read the values of the trigonometric functions from the triangle.

\(\sin 45^\circ = \dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{hypotenuse}}\) = \(\boxed{\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}}\) \(\cos 45^\circ = \dfrac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{hypotenuse}}\) = \(\boxed{\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}}\) \(\tan 45^\circ = \dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{adjacent}}\) = \(\boxed{1}\)

\(\csc 45^\circ = \dfrac{\text{hypotenuse}}{\text{opposite}}\) = \(\boxed{\sqrt{2}}\) \(\sec 45^\circ = \dfrac{\text{hypotenuse}}{\text{adjacent}}\) = \(\boxed{\sqrt{2}}\) \(\cot 45^\circ = \dfrac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{opposite}}\) = \(\boxed{1}\)

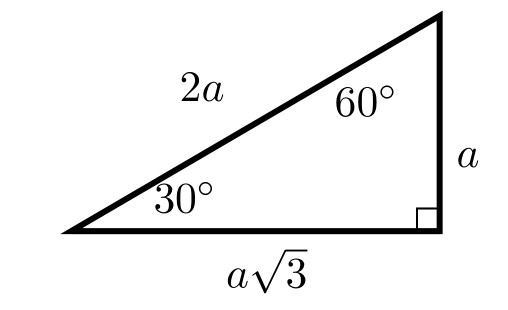

We can also construct a triangle for 30° and 60° angles. To do this we start with an equilateral triangle where each side has length 2. We then cut it in half vertically to create two right triangles with 30° and 60° angles as shown in Figure 1.12. To find the height of the triangle, \(\sqrt{3}\), we once again used the Pythagorean theorem. With this triangle we can now find the values of the six trigonometric functions for both 30° and 60° angles.

\(\sin 30^\circ = \dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{hypotenuse}}\) = \(\boxed{\dfrac{1}{2}}\) \(\cos 30^\circ = \dfrac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{hypotenuse}}\) = \(\boxed{\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}}\) \(\tan 30^\circ = \dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{adjacent}}\) = \(\boxed{\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{3}}}\)

\(\csc 30^\circ = \dfrac{\text{hypotenuse}}{\text{opposite}}\) = \(\boxed{2}\) \(\sec 30^\circ = \dfrac{\text{hypotenuse}}{\text{adjacent}}\) = \(\boxed{\dfrac{3}{\sqrt{3}}}\) \(\cot 30^\circ = \dfrac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{opposite}}\) = \(\boxed{\sqrt{3}}\)

\(\sin 60^\circ = \dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{hypotenuse}}\) = \(\boxed{\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}}\) \(\cos 60^\circ = \dfrac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{hypotenuse}}\) = \(\boxed{\dfrac{1}{2}}\) \(\tan 60^\circ = \dfrac{\text{opposite}}{\text{adjacent}}\) = \(\boxed{\sqrt{3}}\)

\(\csc 60^\circ = \dfrac{\text{hypotenuse}}{\text{opposite}}\) = \(\boxed{\dfrac{3}{\sqrt{3}}}\) \(\sec 60^\circ = \dfrac{\text{hypotenuse}}{\text{adjacent}}\) = \(\boxed{2}\) \(\cot 60^\circ = \dfrac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{opposite}}\) = \(\boxed{\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{3}}}\)

Note that we could have done this with a square or equilateral triangle with side length \(a\) and still have come up with the same ratios. Figure 1.13 shows the two triangles and our trigonometric ratios are summarized in the table. The angles are presented in both degrees and radians. Here we will simplify and rationalize denominators where possible. If our ratio is \(\frac{a}{a\sqrt{2}}\) we will move the \(\sqrt{2}\) to the numerator by multiplying by \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{2}}\) to get \(\frac{a\cdot \sqrt{2}}{a\sqrt{2} \cdot \sqrt{2}} = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\).

Identities

We can similarly show that \(\cot \theta = \dfrac{\cos \theta}{\sin \theta}\).

These properties in Example 1.2.7 are true no matter what angle we use. When you have an equation that is always true it is known as an identity. We will see through the course of this book that there are many identities that can be formed using the 6 trigonometric functions.

Notice that the trigonometric functions come in reciprocal pairs. The cosecant is the reciprocal of the sine, the secant is the reciprocal of the cosine and the cotangent is the reciprocal of the tangent. These reciprocal relations are presented below.

There is a set of important identities known as the Pythagorean identities. They come from using the Pythagorean theorem on the trigonometric functions. We will state them here and then prove them.

We should say something about the notation here. When we write \(\sin^2 \theta\) what we mean is \(\left(\sin \theta\right)^2\).

We can similarly show that \(\displaystyle 1+ \cot^2 \theta = \csc^2 \theta\).

Note: The relations and identities presented in this section appear frequently in our study of trigonometry and it will be useful to memorize them.

1.2 Exercises

Fill in the missing word(s) for the fractions.

\(\displaystyle \sin \theta = \frac{\text{\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_}}{\text{hypotenuse}}\)

\(\displaystyle \csc \theta = \frac{\text{\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_}}{\text{opposite}}\)

\(\displaystyle \cos \theta = \frac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_}}\)

\(\displaystyle \sec \theta = \frac{\text{\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_}}{\text{adjacent}}\)

\(\displaystyle \tan \theta = \frac{\text{\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_}}{\text{adjacent}}\)

\(\displaystyle \cot \theta = \frac{\text{\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_}}{\text{\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_}}\)

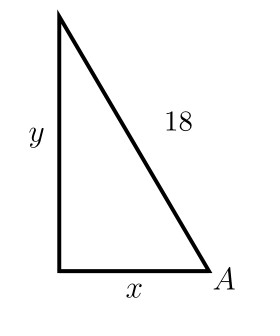

For Exercises 2-9, find the values of all six trigonometric functions of angles \(A\) and \(B\) in the right triangle \(\triangle ABC\) in Figure 1.14.

Figure 1.14

\(a = 5\), \(b = 6\)

\(a = 5\), \(c = 6\)

\(a = 6\), \(b = 10\)

\(a = 6\), \(c = 10\)

\(a = 7\), \(b = 24\)

\(a = 1\), \(c = 2\)

\(a = 5\), \(b = 12\)

\(b = 24\), \(c = 36\)

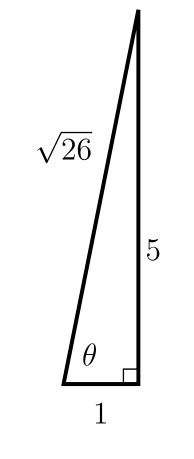

For Exercises 10-17, find the values of the other five trigonometric functions of the acute angle \(0 \leq \theta \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\) given the indicated value of one of the functions.

\(\sin \theta = \frac{3}{4}\)

\(\cos \theta = \frac{3}{4}\)

\(\tan \theta = \frac{3}{4}\)

\(\cos \theta = \frac{1}{3}\)

\(\tan \theta = \frac{12}{5}\)

\(\cos \theta = \frac{\sqrt{5}}{5}\)

\(\sin \theta = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{3}\)

\(\cos \theta = \frac{3}{\sqrt{17}}\)

Suppose that for acute angle \(\theta\) you know that \(\sin \theta = x\). Find a simplified algebraic expression for both \(\cos \theta\) and \(\tan \theta\). (Hint: draw a triangle where the ratio of the opposite to the hypotenuse is \(\frac{x}{1}\).)

For Exercises 19-24, use the special triangles to fill in the following table. (\(0 \leq \theta \leq 90^\circ\), \(0 \leq \theta \leq \pi/2\))

| Function | \(\theta\) (deg) | \(\theta\) (rad) | Function Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19. | \(\sin \theta\) | \(45^\circ\) | ||

| 20. | \(\sec \theta\) | \(60^\circ\) | ||

| 21. | \(\tan \theta\) | \(\dfrac{\pi}{6}\) | ||

| 22. | \(\csc \theta\) | \(\dfrac{\pi}{4}\) | ||

| 23. | \(\cot \theta\) | \(1\) | ||

| 24. | \(\cos \theta\) | \(\dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) |

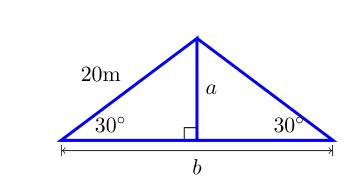

Using the special triangles, determine the exact value of side \(a\) and side \(b\) in Figure 1.15. Express your answer in simplified radical form.

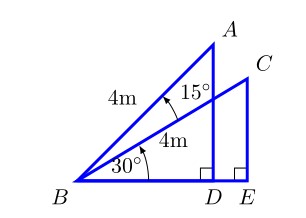

Using the special triangles, determine the exact value of segment \(\overline{DE}\) in Figure 1.16. Segments \(\overline{BA}\) and \(\overline{BC}\) have length 4. Express your answer in simplified radical form.

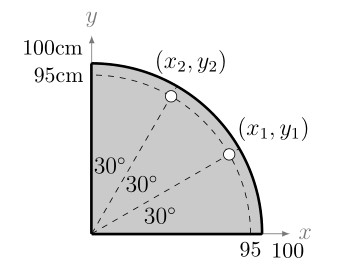

- A metal plate has the form of a quarter circle with a radius of 100 cm. Two 3 cm holes are to be drilled in the plate 95 cm from the corner at 30° and 60° as shown in Figure 1.17. To use a computer controlled milling machine you must know the Cartesian coordinates of the holes. Assuming the origin is at the corner what are the coordinates of the holes \((x_1,y_1)\) and \((x_2,y_2)\)? (Round to 3 decimal places.)

Figure 1.17: Problem 27

1.3 Trigonometric Functions of Any Angle

So far we have only looked at trigonometric functions of acute (less than 90°) angles. We would like to be able to find the trigonometric functions of any angle.

To do this follow these steps:

- Draw the angle in standard position on the coordinate axes

- Draw a reference triangle and find the reference angle

- Label the reference triangle

- Write down the answer

OR use your calculator.

Figure 1.18: Cartesian plane divided into 4 quadrants

Note: Your calculator will only give you decimal approximations but, where possible, the answers will be exact. For example if you ask your calculator for \(\cos(30^\circ)\) it might return an answer of 0.86602540378 whereas in this text we will present the answer as \(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\).

Before we can talk about reference triangles and reference angles we need to review the coordinate plane. We can define the trigonometric functions of any angle in terms of Cartesian coordinates. You will recall that the \(xy\)-coordinate plane (Cartesian coordinates) consists of points represented as coordinate pairs \((x, y)\) of real numbers. The plane is divided into 4 quadrants called quadrants 1 through 4 (see Figure 1.18). These are often abbreviated QI, QII, QIII and QIV or 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th.

Reference Angles

Figure 1.19 is a reference angle and triangle in the 2nd quadrant. Figure 1.20 is a reference angle and triangle in the 4th quadrant.

The size of the reference angle in the second quadrant (QII) will be \(180 - \theta\) or \(\pi - \theta\) depending on whether the angle is given in degrees or radians respectively.

The size of the reference angle in the fourth quadrant (QIV) will be \(360 - \theta\) or \(2\pi - \theta\) depending on whether the angle is given in degrees or radians respectively.

What formula will give you the size of a reference angle in the third quadrant?

The six trigonometric functions can be defined in the same way as before but now the lengths are read off the reference triangle. Since the coordinates \((x, y)\) can be negative, when we take the ratios of the sides of the triangle we often find negative results. The distance from the origin to the point \((x, y)\) is the hypotenuse and is always a positive value (\(r>0\)). The trigonometric functions of \(\theta\) are as follows.

Now we will use these reference angles to find the values of some trigonometric functions. We can follow the steps outlined at the beginning of the section:

- Draw the angle in standard position on the coordinate axes

- Draw a reference triangle and find the reference angle

- Label the reference triangle

- Write down the answer

What this has shown us is that we can determine the sign of the trigonometric functions by the quadrant of the terminal side. When constructing the reference triangle, the hypotenuse is always positive but the two legs can be either positive or negative depending on where the triangle is drawn. In the first quadrant both legs are positive, in the second quadrant the adjacent side (\(x\)) is negative (Figure 1.23(a)), in the third quadrant both legs (\(x\) and \(y\)) are negative (Figure 1.23(b)) and in QIV the opposite side (\(y\)) is negative. Since the trigonometric functions are ratios of the sides of the reference triangle then All the functions are positive in the first quadrant, the Sine is positive in the second, the Tangent is positive in the third and the Cosine is positive in the fourth. This information is summarized in Figure 1.24. The mnemonic All Students Take Calculus tells you which function is positive in which quadrant.

Figure 1.24: The signs of the trigonometric functions

Since \(\csc \theta = \dfrac{1}{\sin \theta}\) then the cosecant has the same sign as the sine function. Similarly \(\sec \theta\) has the same sign as \(\cos \theta\) and \(\cot \theta\) has the same sign as \(\tan \theta\).

1.3 Exercises

In which quadrant(s) do sine and cosine have the same sign?

In which quadrant(s) do sine and cosine have the opposite sign?

In which quadrant(s) do sine and tangent have the same sign?

In which quadrant(s) do sine and tangent have the opposite sign?

In which quadrant(s) do cosine and tangent have the same sign?

In which quadrant(s) do cosine and tangent have the opposite sign?

For Exercises 7-11, find the reference angle for the given angle.

\(127^\circ\)

\(250^\circ\)

\(-250^\circ\)

\(882^\circ\)

\(-323^\circ\)

Let \((-3, 4)\) be a point on the terminal side of \(\theta\). Find the exact values of \(\sin \theta\), \(\cos \theta\), and \(\tan \theta\) without a calculator.

Let \((-12, -5)\) be a point on the terminal side of \(\theta\). Find the exact values of \(\sin \theta\), \(\cos \theta\), and \(\tan \theta\) without a calculator.

Let \((8, -15)\) be a point on the terminal side of \(\theta\). Find the exact values of \(\sin \theta\), \(\cos \theta\), and \(\tan \theta\) without a calculator.

For Exercises 15-24:

- Find the reference angle for the given angle.

- Draw the reference triangle and label the sides.

- Find the exact values of \(\sin \theta\), \(\cos \theta\), and \(\tan \theta\) without a calculator.

\(30^\circ\)

\(135^\circ\)

\(-150^\circ\)

\(-45^\circ\)

\(945^\circ\)

\(\frac{\pi}{4}\)

\(-\frac{2\pi}{3}\)

\(\frac{7\pi}{6}\)

\(-\frac{29\pi}{3}\)

\(\frac{29\pi}{4}\)

For Exercises 25-29, find the values of \(\sin \theta\) and \(\tan \theta\) given the following \(\cos \theta\) values.

\(\cos \theta = \frac{3}{4}\)

\(\cos \theta = -\frac{3}{4}\)

\(\cos \theta = \frac{1}{4}\)

\(\cos \theta = 0\)

\(\cos \theta = 1\)

For Exercises 30-34, find the values of \(\cos \theta\) and \(\tan \theta\) given the following \(\sin \theta\) values.

\(\sin \theta = \frac{3}{4}\)

\(\sin \theta = -\frac{3}{4}\)

\(\sin \theta = \frac{1}{4}\)

\(\sin \theta = 0\)

\(\sin \theta = 1\)

For Exercises 35-39, find the values of \(\sin \theta\) and \(\cos \theta\) given the following \(\tan \theta\) values.

\(\tan \theta = \frac{3}{4}\)

\(\tan \theta = -\frac{3}{4}\)

\(\tan \theta = \frac{1}{4}\)

\(\tan \theta = 0\)

\(\tan \theta = 1\)

For Exercises 40-44, find the values of the six trigonometric functions of \(\theta\) with the given restriction.

| Function Value | Restriction | |

|---|---|---|

| 40. | \(\sin \theta = \dfrac{15}{17}\) | \(\tan \theta < 0\) |

| 41. | \(\sec \theta = -\dfrac{15}{12}\) | \(\sin \theta < 0\) |

| 42. | \(\tan \theta = \dfrac{20}{21}\) | \(\csc \theta > 0\) |

| 43. | \(\cos \theta = -\dfrac{20}{21}\) | \(\csc \theta > 0\) |

| 44. | \(\sec \theta\) is undefined | \(\pi \leq \theta \leq \frac{3\pi}{2}\) |

For Exercises 45-54, use a calculator to evaluate the following trigonometric functions. Round your answer to 4 decimal places.

\(\sin 127^\circ\)

\(\cos 250^\circ\)

\(\csc\left(-250^\circ\right)\)

\(\cot 882^\circ\)

\(\sec\left(-323^\circ\right)\)

\(\tan \left( \dfrac{\pi}{5}\right)\)

\(\cot \left( -\dfrac{\pi}{5}\right)\)

\(\csc \left( \dfrac{\pi}{5}\right)\)

\(\cot \pi\)

\(\sec\left(-\dfrac{14}{5}\right)\)

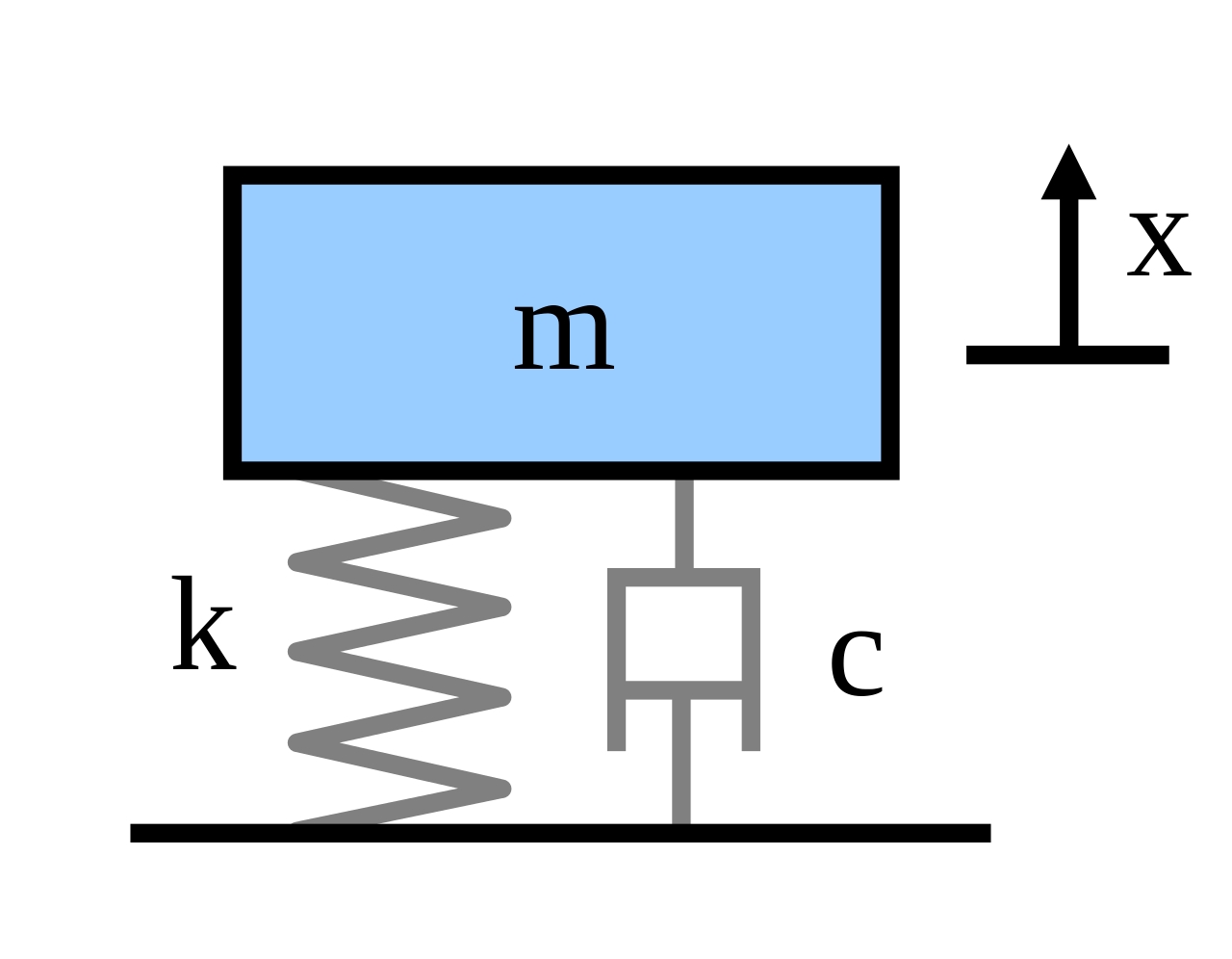

In engineering the motion of the spring-mass-damper system can be modeled by the equation \[x = \sqrt{221} e^{-0.2 t} \cos \left( 14t - 0.343 \right)\] where \(x\) is the position of the mass relative to equilibrium (no motion), \(t\) is the time measured in seconds after the system is set into motion and the angles are in radians. Find the positions \(x\) of the mass when the time is \(t = 1\) sec, \(t = 5\) sec, \(t = 10\) sec, and \(t = 20\) sec.

What does a negative position mean?

1.4 The Unit Circle

Figure 1.25: A circle of radius 1 with a reference triangle drawn in the first quadrant.

Every point \((x, y)\) on the unit circle corresponds to some angle \(\theta\). For example:

| Point \((x, y)\) | Angle \(\theta\) |

|---|---|

| \((1, 0)\) | 0° or 0 |

| \((0, 1)\) | 90° or \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) |

| \((-1, 0)\) | 180° or \(\pi\) |

| \((0, -1)\) | 270° or \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) |

We can define trigonometric functions based on the coordinates of the point on the unit circle which corresponds to the angle. Notice that since the circle has radius 1 the reference triangle in Figure 1.25 above has hypotenuse 1, height length \(y\) and base length \(x\). We can now use the techniques from Section 1.3 to define the six trigonometric functions:

We can use the two special triangles we looked at in Section 1.2 to fill in the unit circle for many “standard” angles. In the following diagram, each point on the unit circle is labeled with its coordinates \((x, y) = (\cos \theta, \sin \theta)\) (exact values) and with the angle in degrees and radians.

Figure 1.26: The Unit Circle has radius 1. The coordinates on the circle give you the values of the cosine and the sine of the angle \(\theta\). \((x, y) = (\cos \theta, \sin \theta)\)

For any trigonometry problem involving one of the nice angles (multiples of 30°, 45°, or 60°) you can either use the unit circle or the triangle techniques in Section 1.3.

Domain and Period of sine, cosine and tangent

Recall that the domain of a function \(f(x)\) is the set of all numbers \(x\) for which the function is defined. For example, the domain of \(f(x) = \sin x\) and \(f(x) = \cos x\) is the set of all real numbers, whereas the domain of \(f(x) = \tan x\) is the set of all real numbers except \(x=\pm\,\frac{\pi}{2}\), \(\pm\,\frac{3\pi}{2}\), \(\pm\,\frac{5\pi}{2}\), \(\ldots\).

The range of a function \(f(x)\) is the set of all values that \(f(x)\) can take over its domain. For example, the range of \(f(x)=\sin x\) and \(f(x) = \cos x\) is the set of all real numbers between \(-1\) and \(1\) (i.e. the interval \(\left[-1,1\right]\)), whereas the range of \(f(x) = \tan x\) is the set of all real numbers. (Why?)

Recall that by adding or subtracting \(360^\circ\) or \(2\pi\) to any angle you get back to the same angle on the graph (coterminal). So the following relationships are true:

\[\sin (x) = \sin (x + 2\pi) \qquad \text{and} \qquad \cos (x) = \cos(x+2\pi) \tag{2}\]

In fact any integer multiple of \(2\pi\) can be added to the angle to arrive at a coterminal angle. Multiples of \(2\pi\) are represented as

\[2n\pi, \qquad \text{where}~ n \in \left\{ \ldots, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots \right\}.\]

The integers are represented by \(\mathbb{Z}\): \(\mathbb{Z} = \left\{ \ldots, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots \right\}\). We can abbreviate the above multiples of \(2\pi\) as:

\[2n\pi, ~\text{where}~ n \in \mathbb{Z}.\]

The relationships in equation (Equation 2) are said to be periodic with period \(2\pi\).

\(f(x) = \sin x\) and \(f(x) = \cos x\) are periodic with period \(2\pi\) and \(f(x) = \tan x\) is periodic with period \(\pi\).

Recall from algebra that even and odd functions have special properties when the sign of the variable is changed. An even function satisfies the property \(f(x) = f(-x)\) so it returns the same result with both positive and negative \(x\) values. An odd function is one that has the property \(-f(x) = f(-x)\) so the function returns the negative result for \(-x\). The cosine and sine satisfy the same properties where:

You can see this by examining the corresponding values on the unit circle.

We can also construct what are known as cofunction identities which relate two different functions.

1.4 Exercises

Fill in the blanks for problems 1-8.

Every point on the unit circle is \((x, y) =\) _______________ for some angle \(\theta\).

The equation for the unit circle is _______________.

The unit circle is a circle of radius _______________.

Functions that repeat values at a regular interval are called _______________.

An even function satisfies the property _______________.

The range of \(y=\cos x\) is _______________.

The range of \(y=\tan x\) is _______________.

An odd function satisfies the property _______________.

For Exercises 9-18, find the corresponding point \((x,y)\) on the unit circle and then find the six trigonometric functions for the given angle.

\(\alpha = 150^\circ\)

\(\theta = 135^\circ\)

\(\gamma = -135^\circ\)

\(\beta = 720^\circ\)

\(\alpha = -540^\circ\)

\(\alpha = \dfrac{3\pi}{4}\)

\(\theta = \dfrac{5\pi}{3}\)

\(\gamma = -\dfrac{5\pi}{3}\)

\(\beta = 17\pi\)

\(\alpha = -\dfrac{11\pi}{2}\)

Suppose \(\sin(t) = -\dfrac{3}{4}\). Find:

\(\sin(-t)\)

\(\csc(-t)\)

\(\sec(90^\circ-t)\)

\(\cos\left(t + \frac{\pi}{2}\right)\)

Suppose \(\tan(t) = -\dfrac{3}{4}\). Find:

\(\tan(-t)\)

\(\cot(-t)\)

\(\tan(t-90^\circ)\)

\(\tan\left(t + \frac{\pi}{2}\right)\)

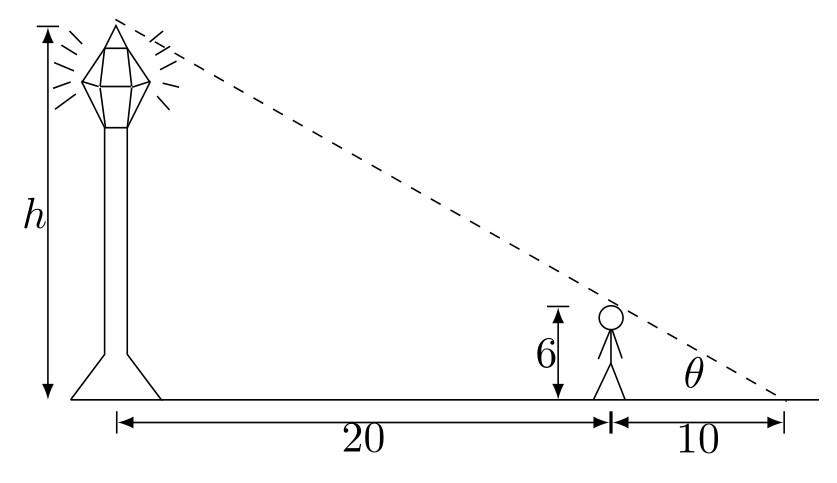

1.5 Applications and Models

In general, a triangle has six parts: three sides and three angles. Solving a triangle means finding the unknown parts based on the known parts. In the case of a right triangle, one part is always known: one of the angles is 90°. Later we will see how to do this when we do not have a right triangle. We also know that the angles of a triangle add up to 180°.

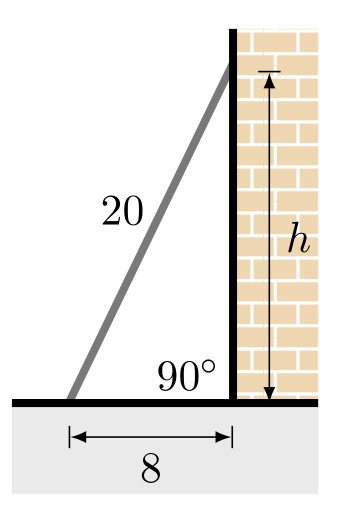

Figure 1.27

1.5 Exercises

Figure 1.29 Problems 1-8

For Exercises 1-8, solve the right triangle \(\triangle ABC\) in Figure 1.29 using the given information.

\(A = 35^\circ\), \(b = 6\)

\(a = 5\), \(B = 6^\circ\)

\(a = 1\), \(B = 36^\circ\)

\(A = 6^\circ\), \(c = 10\)

\(c = 7\), \(B = 24^\circ\)

\(A = 1^\circ\), \(a = 2\)

\(A = \dfrac{\pi}{4}\), \(b = 12\)

\(B = \dfrac{\pi}{3}\), \(c = 36\)

Figure 1.30: Problems 9-11

For Exercises 9-11, find the length of \(x\) in Figure 1.30.

\(\alpha = 55^\circ\;30'\), \(\beta = 62^\circ\;30''\), \(h = 15\)

\(\alpha = 25^\circ\), \(\beta = 30^\circ\), \(h = 15\)

\(\alpha = \pi/5\), \(\beta = \pi/3\), \(h = 15\)

To find the height of a tree, a person walks to a point 30 feet from the base of the tree, and measures the angle from the ground to the top of the tree to be 29°. Find the height of the tree.

The angle of elevation to the top of a building is found to be 9 degrees from the ground at a distance of 1 mile from the base of the building. Using this information, find the height of the building.

The angle of elevation to the top of the Space Needle in Seattle is found to be 31 degrees from the ground at a distance of 1000 feet from its base. Using this information, find the height of the Space Needle.

A 33-ft ladder leans against a building so that the angle between the ground and the ladder is 60°. How high does the ladder reach up the side of the building?

A 23-ft ladder leans against a building so that the angle between the ground and the ladder is 70°. How high does the ladder reach up the side of the building?

As the angle of elevation from the top of a tower to the sun decreases from 64° to 49° during the day, the length of the shadow of the tower increases by 92 ft along the ground. Assuming the ground is level, find the height of the tower.

Find the length \(c\) in the diagram below. (Two triangles with vertical height 115, base angles 20° and 25°, unknown base length \(c\))

Find the length \(c\) in the diagram below. (Two triangles with vertical height 75, base angles 25° and 37°, unknown base length \(c\))

Two banks of a river are parallel, and the distance between two points \(A\) and \(B\) along one bank is 500 ft. For a point \(C\) on the opposite bank, \(\angle BAC = 56^\circ\) and \(\angle ABC = 41^\circ\). What is the width \(w\) of the river? (Hint: Divide \(\overline{AB}\) into two pieces.)

A person standing on the roof of a 100 m building is looking towards a skyscraper a few blocks away, wondering how tall it is. She measures the angle of depression from the roof of the building to the base of the skyscraper to be 20° and the angle of elevation to the top of the skyscraper to be 40°. Calculate the distance between the buildings \(x\) and the height of skyscraper \(h\). See Figure 1.31.

Figure 1.31: Problem 21

- 2200 years ago the Greek Aristarchus realized that using trigonometry it is possible to calculate the distance to the sun. Let \(O\) be the center of the earth and let \(A\) be the center of the moon. Aristarchus began with the premise that, during a half moon, the moon forms a right triangle with the Sun and Earth. By observing the angle between the Sun and Moon, \(\phi=89.83^\circ\) and knowing the distance to the moon, about 239,000 miles, it is possible to estimate the distance from the center of the earth to the sun. Estimate the distance to the sun using these values. See Figure 1.32.

Figure 1.32: Problem 22

A plane is flying 2000 feet above sea level toward a mountain. The pilot observes the top of the mountain to be \(\alpha=18^\circ\) above the horizontal, then immediately flies the plane at an angle of \(\beta=20^\circ\) above horizontal. The airspeed of the plane is 100 mph. After 5 minutes, the plane is directly above the top of the mountain. How high is the plane above the top of the mountain (when it passes over)? What is the height of the mountain?

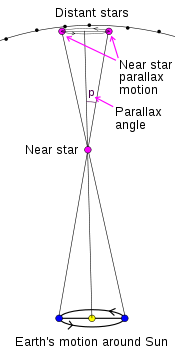

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight. (A simple everyday example of parallax can be seen in the dashboard of motor vehicles that use a needle-style speedometer gauge. When viewed from directly in front, the speed may show exactly 60; but when viewed from the passenger seat the needle may appear to show a slightly different speed, due to the angle of viewing.) Parallax can be used to calculate the distance to near stars. By measuring the distance a star moves when taking two observations when the earth is on opposite sides of the sun we can calculate the parallax angle. Figure 1.33 shows the parallax angle labeled \(p\). Knowing that the distance from the earth to the sun is about 92,960,000 miles how far is it from the sun to a star that creates a parallax angle \(p = 1''\) (one second)? This is a distance known as 1 parsec.

Figure 1.33: Problem 24

Footnotes

The angle of elevation is the angle made from the horizontal looking up to some object. Similarly the angle of depression is the angle from the horizontal looking down to some object.↩︎

The grade is the slope (rise over run) of the road. When expressed as a percentage: grade = \(100\left(\frac{\text{rise}}{\text{run}}\right)\)↩︎