3.1 Graphs of Polynomials

Definition: A polynomial of degree \(n\) is a function of the form:

\[f(x) = a_n x^n + a_{n-1} x^{n-1} + \cdots + a_1 x + a_0\]

where \(a_n \neq 0\) and the coefficients \(a_n, a_{n-1}, \ldots, a_1, a_0\) are real numbers.

The leading term is \(a_n x^n\).

The leading coefficient is \(a_n\).

The degree of the polynomial is \(n\).

The constant term is \(a_0\)

Find the leading term, the leading coefficient, the degree and the constant term for the polynomial \(f(x) = x^4 -x^3-20x^2-3x^6+12\)

General shape and long run behavior

Odd exponent leading term: \(x\), \(x^3\), \(x^5\), etc

Even exponent leading term: \(x^2\), \(x^4\), \(x^6\), etc

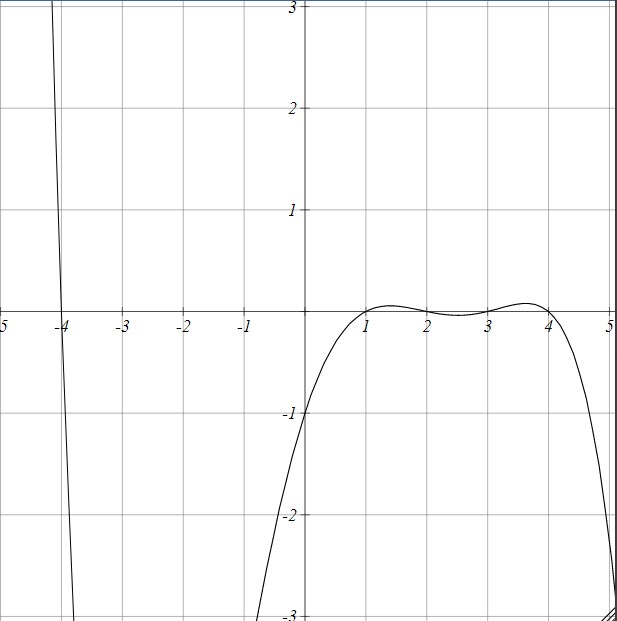

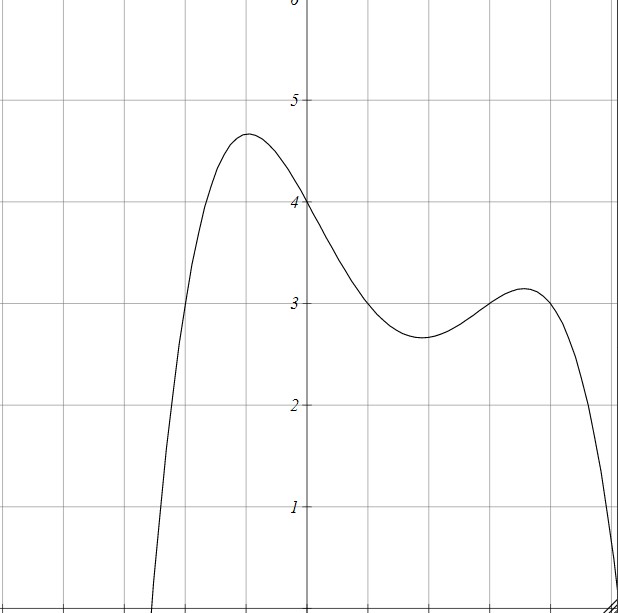

Find the minimum degree for the following functions.

Odd

Even

For polynomial functions of higher degree than 2 we will primarily be concerned with finding intercepts (zeros). The best way to find zeros is to FACTOR.

Find all zeros of \(f(x) = 5x^4 -x^3-20x^2\)

To find zeros you must set the function equal to zero. Do not do this unless you are looking for zeros.

\[\begin{align*}

x^4 -x^3-20x^2 &= 0\\

x^2(x^2-x-20) &= 0\\

x^2(x-5)(x+4) &= 0

\end{align*}\]

Now we have three things multiplied together that equal zero so one of them must be zero.

\[x^2 = 0 \qquad \text{OR} \qquad x-5=0 \qquad \text{OR} \qquad x + 4 = 0\]

Find the zeros and intercepts of \(f(x) = 49 - r^3\)

Find the zeros and intercepts of \(h(x)=2x^4-2x^2-40\)

If you know the zeros of the polynomial you can easily write the polynomial.

Find a polynomial of degree 3 with the following zeros: \(x\) = -2, 0, 6.

Multiplicity

Definition: Suppose \(f(x)\) is a polynomial function and \(m\) is a natural number. If \((x - c)^m\) is a factor of \(f(x)\) but \((x - c)^{m+1}\) is not, then we say \(x = c\) is a zero of multiplicity \(m\).

Suppose \(f(x)\) is a polynomial function and \(x = c\) is a zero of multiplicity \(m\).

If \(m\) is even, the graph of \(y = f(x)\) touches and rebounds from the \(x\)-axis at \((c,0)\).

If \(m\) is odd, the graph of \(y = f(x)\) crosses through the \(x\)-axis at \((c,0)\).

Create a polynomial \(P(x)\) which has the desired characteristics. Leave the polynomial in factored form. Sketch.

- degree 4

- root of multiplicity 2 at \(x=1\)

- roots of multiplicity 1 at \(x=0\) and \(x=-3\)

- the graph passes through the point \((2,20)\)

Find a formula for the polynomial \(P(x)\) which has the desired characteristics. Leave the polynomial in factored form. Sketch.

- degree 9

- leading coefficient 1

- root of multiplicity 5 at \(x=0\)

- root of multiplicity 2 at \(x=11\)

- root of multiplicity 2 at \(x=-5\)

3.2 The Factor Theorem and the Remainder Theorem

We can use long division to divide polynomials the same way we use long division to divide integers.

Simplify this fraction: \(\frac{x^4+5x^3+6x^2-x-2}{x+2}\)

So we know that:

\[\frac{x^4+5x^3+6x^2-x-2}{x+2} = x^3+3x^2-1\]

More specifically we have a factor of \(f(x)=x^4+5x^3+6x^2-x-2\).

\[\boxed{x^4+5x^3+6x^2-x-2 = (x^3+3x^2-1)(x+2)}\]

\[\frac{5x^3+18x^2 +8x -6}{x+3}\]

So we know that:

\[\frac{5x^3+18x^2 +8x -6}{x+3} = 5x^2+3x-1 + \frac{-3}{x+3}\]

If we write it with no denominators we get an expression of the form:

\[\boxed{5x^3+18x^2 +8x -6 = (5x^2+3x-1)(x+3)-3}\]

This form illustrates the theorem known as The Division Algorithm which states that any two polynomials \(P(x)\) and \(D(x)\) (where \(D(x)\) is of lower degree) can be written as:

\[P(x) = D(x) \cdot q(x) + r(x)\]

More formally:

If \(P(x)\) and \(D(x)\) are polynomials such that \(D(x) \neq 0\) and the degree of \(D(x)\) is less than or equal to the degree of \(P(x)\), there exist unique polynomials \(q(x)\) and \(r(x)\) such that:

\[P(x) = D(x) \cdot q(x) + r(x)\]

OR

\[\frac{P(x)}{D(x)} = q(x) + \frac{r(x)}{D(x)}\]

Synthetic Division (The easy way to divide)

Divide using synthetic division: \(\frac{5x^3+18x^2 +8x -6}{x+3}\)

Suppose \(p(x)\) is a polynomial of degree at least 1 and \(c\) is a real number. When \(p(x)\) is divided by \(x-c\) the remainder is \(p(c)\).

Use the remainder theorem to find the value of \(p(-3)\) where:

\[p(x) = 5x^3+18x^2 +8x -6\]

3.3 Real Zeros of a Polynomial

Suppose we know that \(x = -2\) is a zero of the polynomial \(f(x) = 2x^3+x^2-5x+2\). Find all the zeros of the polynomial and write it in factored form.

Solution: Since we know that \(x=-2\) is a zero then we know that:

\[f(x) = 2x^3+x^2-5x+2 = (x+2) \cdot q(x)\]

and we can use synthetic division to find \(q(x)\).

Use synthetic division to divide \(\frac{-3x^4}{x+2}\)

Given that \((x+2)\) and \((x-4)\) are factors of \(f(x)=8x^4-14x^3-71x^2-10x+24\) find all the zeros of \(f(x)\).

If the polynomial \(f(x)=a_nx^n + a_{n-1}x^{n-1} + \cdots + a_2x^2 +a_1x + a_0\) has integer coefficients, every rational zero of \(f\) has the form:

\[\text{Rational zero} = \frac{p}{q}\]

where \(p\) and \(q\) have no common factors other than 1, and:

- \(p\) = a factor of the constant term \(a_0\)

- \(q\) = a factor of the leading coefficient \(a_n\)

Use the rational roots test to find all the real zeros of:

\[g(x) = 6x^3-7x^2+1\]

(ans. 1, 1/2, -1/3)

Use the rational roots test to find all the real zeros of:

\[p(x) = 12x^3-35x^2+7x+30\]

(ans. 2, 5/3, -3/4)

3.4 Complex Zeros and the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra

Q: What is a complex number?

A: It is a number of the form \(a + bi\) where \(a\) and \(b\) are real numbers and \(i^2 = -1\).

- \(a\) is called the real part

- \(b\) is called the imaginary part

- The conjugate of \(a + bi\) is \(a - bi\)

Properties

- \(a + b~i = c + d~i \qquad \Leftrightarrow \qquad a = c \text{ and } b = d\)

- \((a + b~i) + (c + d~i) = (a + c) + (b + d)~i\)

- \((a + b~i) \cdot (c + d~i) = ac + ad~i + bc~i +bd~i^2 = (ac-bd)+(ad+bc)~i\)

- \((a+b~i)(a-b~i) = a^2 + b^2\)

- \((4+i) +(5+3i)\)

- \((2i+7)-2i\)

- \((3+2i)+(4-i)-(7+i)\)

- \((5+2i)(4-3i)\)

- \(\frac{i}{3+i}\)

- \(\frac{3-5i}{2-i}\)

- \((3-\sqrt{-4})+(-8+\sqrt{-25})\)

- \((\sqrt{-5})(\sqrt{-5})\)

- \((2-\sqrt{-1})(5+\sqrt{-9})\)

- \(\frac{1}{3i}\)

Complex numbers in quadratic equations

Solve for \(x\): \(x^2 + 6x +10 = 0\)

Solve for \(x\): \(x^2 + 1 = 0\)

Solve for \(x\): \(9x^2 - 6x +37 = 0\)

If \(f(x)\) is a polynomial of degree \(n\), where \(n>0\), then \(f\) has precisely \(n\) linear factors:

\[f(x)=a_n(x-c_1)(x-c_2) \cdots (x-c_n)\]

where \(c_1, c_2, \ldots , c_n\) are complex numbers.

Find all the zeros of \(f(x) = (x+5)(x-8)^2\)

Find all the zeros of \(f(t) = (t-3)(t-2)(t-3i)(t+3i)\)

Find a polynomial function of degree 7 with integer coefficients that has ONLY the zeros \(c=4\), \(c=-3i\) and \(c = 3i\)

Find all zeros of \(f(x) = 4x^3 +12x^2 + 11x +6\) given that \(x = -2\) is one of the zeros.

Find all the roots of \(f(x) = x^3-7x^2-x+87\) knowing that \(5+2i\) is a zero.